Motto: “My life has been a continuous struggle to carve out a place for Romania in the life of the world, while also defending its national interests.” Nicolae Titulescu (Romanian diplomat, Foreign Minister, President of the League of Nations 1930-1932)

One of the most known descriptions of the role of diplomacy in international relations belongs to Lord Henry Palmerston, British Prime Minister, in a speech to House of Commons, on 1 March 1848: “We have no eternal allies, and we have no perpetual enemies. Our interests are eternal and perpetual, and those interests it is our duty to follow.” One may be tempted to consider such a cynical definition outdated; however, as French chemist Antoine Lavoisier noted: “In nature nothing is lost, nothing is created, and everything is transformed”.

Today, diplomacy is generally considered as the practices and strategies of conducting negotiations between states and international actors, in order to pursue their interests. Henry Kissinger defined diplomacy as “the art of restraining power”, while Professor Yoav Tenembaum (Tel Aviv University) considers “diplomacy is the art of restraining force”. By creating alliances, partnerships and international cooperation formats, diplomacy increases influence – which is an element of power – and therefore I believe diplomacy may also be seen as the art of increasing power. Effective diplomacy is often associated with the concept of “soft power”, formulated by American political scientist Joseph Nye as being “the ability to influence others and achieve desired outcomes through attraction and persuasion rather than coercion or payment”.

After WW2, key international organizations have been created, most of them in Europe (the continent where both World Wars sparked), with the goal to prevent war and promote cooperation: the United Nations, the Council of Europe, the European Communities (precursors of the European Union), the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe. With the adoption by the UN General Assembly in 1948 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, human rights protection gained global coverage, becoming a “new religion” in diplomacy. As Alain Berset, Secretary General of the Council of Europe, remarked on 3 September 2025: “Massive violations of human rights and international law know no borders. Every violation of international law is a weakening of our values. What happens beyond our geographical borders is also our problem. Because if we were to consider that our values know borders, we would only weaken them”.

One of the first definitions of the profession of diplomat is attributed to Sir Henry Wotton, the envoy of King James VI of England to Venice, in 1604: “An ambassador is an honest gentleman sent to lie abroad for the good of his country”. 200 years later, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Perigord, Napoleon’s foreign policy chief and widely considered one of the most skilled diplomats of all times, noted: A diplomat who says “yes” means “maybe”, a diplomat who says “maybe” means “no”, and a diplomat who says “no” is no diplomat”.

After 33 years in the Romanian diplomatic service, of which almost 23 years as ambassador, I reached to the conclusion that diplomats are made, not born. No one is born with the ability to practice international diplomacy, which requires to understand foreign societies, influence governments, conduct negotiations, anticipate threats and take advantage of opportunities. These skills have to be acquired, and therefore professional diplomatic services require training, tools and resources. Diplomacy is learned from books, from practice and from inspirational role models.

Good diplomats do not confuse information with analyses, and analyses with judgements – which come from knowledge and experience. Good diplomats have the capacity to absorb and process large amounts of information from different sources, communication skills and high integrity. A key asset is credibility, because good diplomats must be able to convince other people to embrace their ideas. Credibility is based on impeccable reputation, which is a strong currency in international relations. Above all, good diplomats must show an unwavering loyalty to their country’s interests. General Charles de Gaulle, whose boldness, resilience, and love of France continue to inspire, once said: “It is by serving one’s homeland that one best serves the universe; the greatest figures in the universal pantheon were first great figures of their country.“ Fifty five years since his passing, this insight remains highly relevant.

Promoting national interests requires both patriotism and global cooperation. As Professor Yuval Noah Harari argued: “There is no contradiction between globalism and patriotism. Patriotism is about taking care of your compatriots, and in the 21st century in order to take good care of your compatriots you must cooperate with foreigners. So, good nationalists should now be globalists. Globalism means a commitment to some global rules. Rules that don’t deny the uniqueness of each nation, but only regulate the relations between nations.” (21 Lessons for the 21st Century)

Modern diplomacy relies on connectivity, fluid networks and collaboration. Thanks to the internet, we live in the age where the audience is always in the same room with us, information technology is now part of diplomacy and the ability to use social media became mandatory attributes of diplomats. With the transition to digital diplomacy, the diplomatic lifestyle which has existed for decades started to fade. But this sense of modernity may impact on the intimacy of diplomatic discussions, because personal chemistry between diplomats is not to be underestimated, and anyone who has spent time in international negotiations can confirm the added value a discreet chat may have for their outcome.

Platforms like X, Instagram, Truth Social or Facebook provide huge amounts of information, together with a huge challenge: “Information is the food of the mind. Too much information just isn’t good for us. If we fold the mind by an enormous amount of information, we don’t give the mind any time to digest it” (Y.N. Harari, 26 August 2025).

Finally, foreign policy cannot be separated from people’s expectations. Quoting Henry Kissinger: “No foreign policy – no matter how ingenious – has any chance of success if it is born in the minds of a few and carried in the hearts of none”. Communication of foreign policy action must therefore go beyond press releases that use specialized vocabulary, and share with the large public how diplomacy promotes their interests. Social media has become an important tool, but it does not represent diplomacy itself. Messages lacking empathy can create the perception that diplomacy mainly consists of privileges and participation in social events. The reality is that good diplomats have more to do with sacrifice and refrain, than with champagne and caviar.

We are in the midst of fundamental transformations in international relations, a period in which the old order is being diluted and the new order has not yet coagulated. Adapting to this reality requires diplomats the courage to break away from reactive patters in foreign policy, generating ideas, anticipating developments, and offering to political leaders solutions for validation. As President John F. Kennedy put it: “Change is the Law of life, and those who look only to the past or present are certain to miss the future”.

Despite all these changes, diplomacy remains the lifeblood of the international system, a center piece for listening to, and understanding the positions of various parties. In the hectic world of today, diplomats are nations’ soldiers of collaboration. To advance their country’s goals and find ways to cooperate with other nations, diplomats sometimes sail in unchartered waters and become promoters of a new concept of globalization.

Instead of conclusions, the words of the President of Romania, Nicusor Dan, at the Annual Meeting of Romanian Diplomacy on 26 August 2025: “Externally, we are witnessing multiple crises for several years now: the war in Ukraine; a global competition more intense, focused on the economy, on resources; technology is becoming increasingly important; hybrid warfare, including in our own part of Europe. In the face of these changes, it is obvious that diplomacy must adapt and I am convinced we have the strength to do so. Our foreign policy must remain predictable and coherent. Membership in the European Union, membership in NATO, the strategic partnership with the United States, respect for the international law and the rules-based global order, dialogue and cooperation with international partners. These are things that we will not change”.

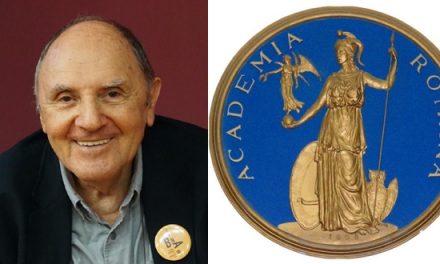

Dr. Ion I. Jinga

Note: The opinions expressed in this article do not bind the official position of the author.